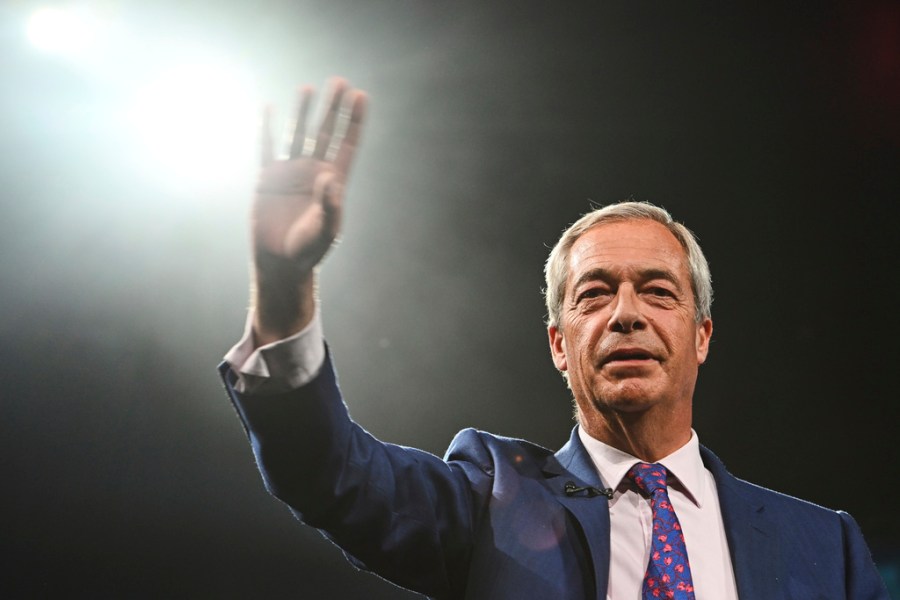

It has been less than 18 months since Britain’s Labor Party won a general election with one of the largest parliamentary majorities in history. Such dominance, which handed the Conservatives their worst election defeat in their 190-year history, should have given Sir Keir Starmer a smooth ride as prime minister for some time. Yet it is the recently formed populist, nationalist Reform UK, led by Nigel Farage, that has led every major opinion poll since April. Now the question is, will Farage be the next Prime Minister of Britain?

There are two ways of looking at the current state of British politics. First, this is an exceptionally volatile period, exacerbated by a sluggish domestic economy, government institutions, and global instability. Mainstream parties have run out of big ideas, forcing voters to look elsewhere, elsewhere.

The past half century has seen long alternating periods of single-party dominance: Conservative (1979–97), Labor (1997–2010) and Conservative again until last year’s defeat. These marathons have weakened the parties ideologically and weakened their leaders. Reform UK was only founded in 2021, it’s still fresh and its leading figures have never held executive office, so they don’t have a track record to defend.

But the premise of this story is that this too shall pass. Reform UK is a fad that seems omnipresent but short-lived. Nigel Farage is a brilliant political communicator, but he is an opportunistic dictator, a thug. He has the quick wit and survival instincts of a sly barker, but his past is riddled with internal strife. If politicians campaign in poetry and govern in prose, Farage is a piece of raw dog.

Britain’s political institutions and culture have deep roots, emerging from the Glorious Revolution of 1688–89, just as a two-party system began to take shape. The Labor Party, founded in 1900, displaced the Liberals as one of the two main contenders in the 1922 general election, but otherwise has a reassuringly solid 350-year history of gradual development. Reform is a passing storm, not a revolution.

The counter-narrative identifies a period of epochal change in which the 2024 elections were the first expression of pressures that have been building for 20 or 30 years. The promised benefits of globalization have been meager; Deindustrialization has broken down traditional working-class communities and created generational unemployment; Immigration has increased rapidly, changing the demography of many areas within a lifetime; And productivity has never recovered from the global financial crisis.

These changes appear to have eroded the class and ideological allegiances of established political parties. “Left” and “right” – terms acquired from sitting in the French National Assembly in 1789 – no longer mean what they did. Farage and Reform UK have navigated these choppy waters with skill, building a new electoral coalition that is socially conservative, anti-immigration, nativist, skeptical of free trade and free markets, and economically interventionist. It has gained the upper hand over the ailing Labor and Conservative dinosaurs.

If the second hypothesis is accurate, Farage may have even greater success ahead. He has captured a significant voting bloc among voters and does not accept guilt for a tired, unsuccessful past. Yet, in practice, he faces an uphill climb to become prime minister.

Reform has only five Members of Parliament out of 650, and came second on another 98 seats, and requires 326 MPs to win a majority in the House of Commons. True, its support in the polls has doubled within a year, from 14.3 percent to nearly 30, but its organization is inadequate, Vetting of candidates is a frequent problemAdditionally, Reform lags behind Labor and the Conservatives in fundraising, despite some high-profile wealthy patrons.

Becoming the largest party in a fragmented House of Commons will require growth of unprecedented scale and speed. The Labor Party won its first seats in Parliament in 1900, but it took more than 20 years to reach three figures, almost 30 years to break 200, and 45 years to gain an absolute majority. If Farage managed all this within five years, “Earthquake” wouldn’t even come close.

Everything is unprecedented until it happens for the first time. In 2017, President Emmanuel Macron’s La République en Marche! It made a strong start, winning 308 seats in the French National Assembly. But Faraz, 61, robust but a drinker and smoker, is impatient and neglectful of detail. He has participated in only one-third of the votes in Parliament, while visiting America a dozen times. Furthermore, while his supporters held “fans” in fanaticism, Six in 10 voters view him unfavorably,

Faraz is talking about his prospects: Self-doubt is not a part of his personality. During President Trump’s state visit to Britain, reform leaders were Asked If the President sees him as the next Prime Minister.

“They know it. All American administrations are deeply aware of it. They see some similarities between what they’ve done and what we’ve done, and you know, we speak the same language.”

it is not impossible. But Labor is only 14 months into government, and Reform may find that good referendums on their own are not enough to start a revolution. If the next election ends with Farage waving outside the famous black doors of 10 Downing Street, it will be one of the biggest shocks in British political history. Possible, but the jury will be out for a while.

Eliot Wilson is a senior fellow for national security at the Coalition for Global Prosperity and co-founder of Pivot Point Group. He was a senior civil servant in the UK House of Commons from 2005 to 2016, including serving as Clerk of the Defense Committee and Secretary of the UK Delegation to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.